As countries around the world gradually re-open and masses of monetary and fiscal stimulus continue to shore up economics, concerns over inflation have increased and bond yields have risen.

Central banks have agreed that a small amount of inflation would be good for the recovery of downturn-hit economies. The US Federal Reserve, for example, has stated that it will tolerate some above-target inflation without tightening policy.

However, some argue that large deficits, some accrued in 2020 alone, act as a deflationary anchor on any inflation concerns.

Global debt, stagnant wage growth and the subdued velocity of money are just three of the reasons why Ariel Bezalel, head of strategy, fixed income at Jupiter, believes that inflation will be a temporary, as oppose to a structural concern.

He said: “While there will undoubtedly be a spike in inflation once economies reopen, we believe this will mostly be due to low base effects and some temporary supply bottlenecks, and that these pressures will fade away after one or two quarters at most.”

Bezalel added that while inflationary pressures will fluctuate, investors will look to longer-term trends.

“Structural inflation everywhere is being kept in check by the combined drivers of too much debt, ‘zombification’ of the corporate sector, ageing demographics and disruption from globalisation, technology, and low-cost labour,” he said.

“The good news is that the success of the vaccine rollout in developed markets has created a level of justified optimism. What remains harder to determine is whether the incredible valuations of both corporate credit and equity can be sustained if central bank support were to be removed.”

He outlined that the “eye-watering” amount of global debt is central to why the uptick in inflation is transitory rather than structural.

Global debt levels climbed $40trn over the last 12 months and, according to the International Monetary Fund, this took the level of world debt to around $280trn.

Bezalel – manager of the £4.3bn Jupiter Strategic Bond fund, said that when government-debt-to GDP reaches 50-60 per cent, this starts to hamper growth and act as a drag on inflation.

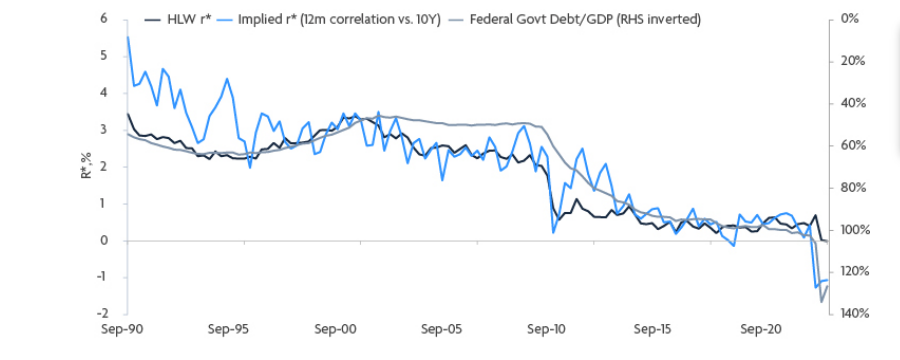

Federal government debt-to-GDP vs rates

Source: Deutsche Bank, US Federal Reserve, Haver Analytics

The graph shows the falling neutral rate of interest in the US, where government debt is around 130 per cent of GDP.

“The euro area, Japan and China have even higher debt levels than the US, which is why we think the US will continue to outperform other major economic zones in terms of economic growth,” he said.

Bezalel referred to the recent surge in the M2 money supply as an argument that monetarist economists use to suggest an imminent rise in inflation.

“We disagree,” he said. “Much of this is likely due to companies drawing down on bank facilities to stay solvent. A better indicator of future inflation would be looking at this rise in money supply against the context of the velocity of money, which remains somewhat subdued.”

He said that, given the level of global debt combined with ageing demographics, it’s unlikely that money velocity will rise in the near term.

He added that the US is currently on course for one-fifth of its population to enter the 65 years+ bracket by the end of the decade and China’s population shrunk for the first time since 1949.

“By 2070, it’s reckoned China’s population will have halved.”

This, he added, has a deflationary effect on consumer spending - as ageing populations typically save more and spend less.

“This is a key reason why we think governments and central banks will need to intervene through fiscal and monetary policy for some time to come, in order to backstop economies as the baby boomer generation continue to retire,” he said.

Weak wage growth will also continue suppress long-term inflation said Bezalel, and for inflation to become an enduring concern, “wage inflation needs to be embedded and accelerating.”

“In the 2010s we had the longest economic boom in post-war history, with full employment, quantitative easing on tap, and corporate tax cuts – yet inflation averaged only 1.6 per cent in the US,” he said.

“If inflation didn’t come through in 2018 when markets were excited about the Trump tax cuts and the labour market was considerably tighter, why should we expect it now?

“It’s worth remembering that for over 30 years, Japan’s central bank has tried everything that Europe and the US have implemented in the last decade or so in order to generate sustainable inflation, to no avail.”